A Time Capsule in Stone

Walking along the Naksan Park section of Seoul City Wall trail, you’ll notice faint inscriptions that look like names carved into the rough granite surface here and there. Curiosity about these mysterious characters led us to explore the 600-year history of the Seoul City Wall(Hanyang Fortress- Hanyang, the old name of Seoul).

The 18.6km Seoul City Wall is more than just a stone barrier. This fortress is a “living history book” spanning seven eras. While China’s Great Wall was a massive border defense against external invaders, Seoul’s City Wall is unique—it cuts through the heart of a modern metropolis, coexisting with the daily lives of Seoul’s citizens. Passing the wall on your morning commute, touching 600-year-old stones during a weekend jog—this is what makes Seoul City Wall special.

Recently, the Netflix animation K-Pop Demon Hunters has gained global popularity, drawing attention to the Seoul City Wall that appears as a backdrop in the series. Particularly memorable is the scene where protagonists Rumi and Jinu share a deep conversation on a hanok* rooftop along Naksan Park’s fortress trail while singing “Free.” Many fans are now visiting the Seoul City Wall to experience that scene firsthand.

* Hanok: traditional Korean house

1396: A 98-Day Miracle

The Desperate Beginning of a New Dynasty

In 1392, Yi Seong-gye, a general of the Goryeo Dynasty, overthrew Goryeo and founded “Joseon.” However, the legitimacy of the new dynasty remained unstable. He decided to move the capital from Gaegyeong to Hanyang* (present-day Seoul). Yi Seong-gye’s reasons for relocating to Hanyang were political, geographical, geomantic*, and economic. Politically, he needed to exclude remnants of Goryeo and establish a foundation for the new dynasty. Geographically, Hanyang’s central location offered convenient transportation and natural mountain barriers advantageous for defense. Additionally, Hanyang was a region with active commerce and trade, holding great economic potential. Yi Seong-gye sought economic development and prosperity by making Hanyang the capital.

At that time, pungsu-jiri* was considered crucial. According to this traditional geomancy, Hanyang was a “natural fortress” surrounded by four mountains—Bugaksan to the north, Naksan to the east, Namsan to the south, and Inwangsan to the west.

In January 1396, King Taejo Yi Seong-gye issued a nationwide decree: “Complete the fortress wall surrounding the capital within 98 days.” This was nearly impossible. Yet approximately 120,000 people from across the nation were mobilized—4% of Joseon’s entire population at the time.

* Hanyang: the capital of the Joseon Dynasty, now Seoul *geomantic: relating to pungsu-jiri (風水地理), Korean traditional geomancy

* pungsu-jiri: traditional Korean geomancy, similar to feng shui

The construction responsibility system of 600 years ago

This massive project proceeded with a unique system. Each region (do*) was assigned a specific section, and workers carved their names into the stones they laid. These are called “gakjaseok*” (inscribed stones). Looking closely at the wall near Changuimun Gate, you can find inscriptions like “Gyeongsang-do Sangju,” “Chungcheong-do Gongju,” and “Jeolla-do Naju.”

This system resembled medieval European guild practices. Each region staked its honor on building the wall to the best of its ability. If their section collapsed, the entire region would be held responsible. However, this was also tremendous suffering for the people. Many lost their lives carrying and stacking massive stones in the winter cold. The Joseon government held annual memorial services for those who died building the wall.

The greatest concentration of inscribed stones can be found at the beginning of the trail from Changuimun to Baegak (Bugaksan). Take on the challenge of reading 600-year-old inscriptions yourself!

*do: provincial administrative division *gakjaseok (刻字石): stones inscribed with the names of the regions or workers responsible for that section

Joseon’s Military Engineering

Genius Use of Terrain

The most remarkable aspect of Seoul City Wall is its perfect utilization of natural topography. The wall was built along the ridges of four mountains. Why? Ridges are natural barriers difficult for enemies to climb. The slopes are steep, and defenders can shoot arrows from elevated positions.

Interestingly, the wall along Namsan is relatively low. The Han River to the south served as a natural defensive line. In contrast, the wall on Bugaksan to the north is higher and more robust—greater preparation was needed against invasions from the north, including the Jurchen people* who would later establish the Qing Dynasty in China.

Walking along the Inwangsan section, the wall suddenly disappears in some places. There, massive rock cliffs stand. Joseon’s engineers didn’t bother building walls there—nature itself was the perfect barrier.

* Jurchen: a Tungusic people who later founded the Qing Dynasty

Chiseong* (雉城): Strategy to Eliminate Blind Spots

Walking along the wall, you’ll notice sections protruding outward at 10-20m intervals. These are “chiseong”—bastions in English. European castles have identical structures. Interestingly, East and West developed this structure independently without contact.

When enemy soldiers reached directly beneath the wall, a blind spot was created where defenders couldn’t see them. Adjacent bastions allowed archers to shoot sideways at these enemies, enabling 360-degree defense.

* chiseong: bastion, a protruding section of the wall

Yeojangs* and Chongan*: The Science of Asymmetric Structure

Walking atop the wall, you’ll see low barriers called “yeojangs”—approximately 1.5m-high walls with small openings called “chongan” or “tagu.” From outside, these appear as small holes, but from inside, the angles are calculated to provide a wide field of vision. This asymmetric structure allowed defenders to see out perfectly while enemies couldn’t see in. Through these openings, Joseon soldiers shot arrows at their foes.

* yeojang (女墻): defensive parapet wall *chongan or tagu: arrow slits or loopholes

Ammun* (暗門): Secret Gates

Beyond the official gates (four great gates and four small gates), Seoul City Wall had hidden entrances called “ammun”—literally “hidden gates.” These served several purposes:

The ammun near Changuimun (Jahamun) still shows traces today. Unlike grand regular gates, it was intentionally designed to be inconspicuous.

* Ammun (暗門): literally “hidden gates,” secret passages

* Water supply: When wells inside the fortress ran dry, water was secretly fetched through ammun

* Reconnaissance: Small forces used them at night to monitor enemy movements

* Emergency escape: Routes for the king to escape in case of defeat

Traces of War

1592: The Tragedy of Imjin War*

* Imjin War (1592-1598): Japanese invasions of Korea led by Toyotomi Hideyoshi

In April 1592, 150,000 Japanese troops led by Toyotomi Hideyoshi invaded Joseon. The invading force that started from Busan reached Seoul in just 20 days. Remarkably, however, Seoul City Wall fell into enemy hands without a single battle.

King Seonjo abandoned his people and fled first. The wall was solid, but there was no one inside to defend it. This incident remains a great shame in Joseon history.

After seven years of war, the fortress was severely damaged—not only from warfare but also from years of neglect and lack of maintenance. In the 30th year of King Sukjong’s reign (1704), the Joseon government began large-scale reconstruction. The walls built then were more sophisticated than before. Stones interlocked more precisely, and bastions and parapets were arranged more scientifically.

Walking the fortress today, compare the textures of the stones. Rough, irregular stones are from the 1396 initial construction, while precisely cut stones are from the 1704 reconstruction.

1950: Scars of the Korean War

The Bugaksan section bears traces of another 20th-century war. Bullet marks are clearly visible throughout the wall. During the 1950 Korean War, fierce battles occurred in this area. Even after the armistice—in 1968—North Korean commandos infiltrated with the mission to assassinate the South Korean president, resulting in a gun battle.

Seoul City intentionally left these historically significant bullet marks unrestored. The fact that a 600-year-old Joseon-era stone wall bears 20th-century modern warfare scars is thought-provoking.

Japanese Colonial Period: Intentional Destruction

After Japan forcibly annexed Korea in 1910, Seoul City Wall faced a serious crisis. In 1915, Japan began large-scale demolition under the pretext of “urban modernization.” However, the real reason was different. The fortress symbolized Korean identity and pride, which Japan wanted to destroy.

Sungnyemun (South Gate) faced demolition in 1907, and Donuimun (West Gate) completely disappeared. About 30% of the wall was destroyed during this period.

In the 1970s-80s, Seoul City began a massive restoration project, rebuilding disappeared walls and repairing damaged sections. However, perfect restoration was impossible. Currently, over 70% of Seoul City Wall has been restored.

Rediscovering Seoul City Wall: From Life’s Boundary to a Path of Peace and Healing

Daily Life of Hanyang Residents and the Fortress

A large bell hung at Bosingak Jonggak announced the opening and closing times of the city gates—33 strikes at dawn and 28 in the evening. Even private gates in residences opened and closed according to these bell sounds.

Hanyang Fortress also served as a boundary between Seoul and the provinces, as well as between life and death. Whether king or commoner, everyone had to be buried outside the fortress after death. For old Seoul residents, the fortress symbolized the “beginning and end” of daily life and human existence.

For those traveling from distant places to the capital, Hanyang Fortress was a symbol of welcome. After walking for days, just glimpsing the fortress from afar brought relief—”Finally, Hanyang!” People of that time enjoyed “sunseong*” (巡城), a recreational activity of walking around the fortress. According to old records, “In spring and summer, Hanyang people would pair up and walk the fortress perimeter, enjoying the scenery inside and out.”

* sunseong: literally “circling the fortress,” a traditional recreational activity

Today, the Seoul City Wall trail has become a daily space for Seoul citizens. Approximately 3 million people visit annually—those hiking for health, couples on dates, and families enjoying Seoul’s scenery.

What the Animation Couldn’t Fully Capture

In 2025, the global success of Netflix’s K-Pop Demon Hunters gave new meaning to Seoul City Wall. The scene where protagonists Rumi and Jinu converse on a hanok rooftop along Naksan Park’s fortress trail imprinted Seoul’s beauty on millions of viewers worldwide.

Visiting Naksan Park’s fortress trail, you can recreate that scene. The view of N Seoul Tower between tranquil hanok rooftops, with the 600-year-old wall harmonizing with the modern city, provides indescribable emotion. Especially at sunset, you can fully feel the meaning of “Free” that Rumi and Jinu shared—Seoul’s identity where tradition and modernity, past and future coexist freely.

The Seoul City Wall shows different beautiful aspects by section, season, and time of day. Since the show’s release, this section has become a “pilgrimage site.” Fans from around the world recreate scenes from the show, naturally developing deeper interest in Korean history and culture.

A Time-Travel Stone Path Through 600 Years

Standing on 600-year-old stones along Inwangsan fortress trail at dusk, looking down at modern high-rise buildings in the distance, you feel all these times layered upon one path—the wall Yi Seong-gye built in 98 days, the stone barrier that witnessed the tragedy of Imjin War, the fortress that took Korean War bullets, and now what K-Pop Demon Hunters fans pilgrimage to visit.

Listed on UNESCO’s World Heritage tentative list, Seoul City Wall is no longer a barrier against enemies. Instead, it has become a “space of connection”—linking past and present, connecting Koreans with foreigners, harmonizing tradition with modernity.

Now it’s your turn to walk the fortress, touch 600-year-old stones with your own hands, look down at the city the wall once defended, and experience a time journey through 600 years.

Recommended Hiking Routes

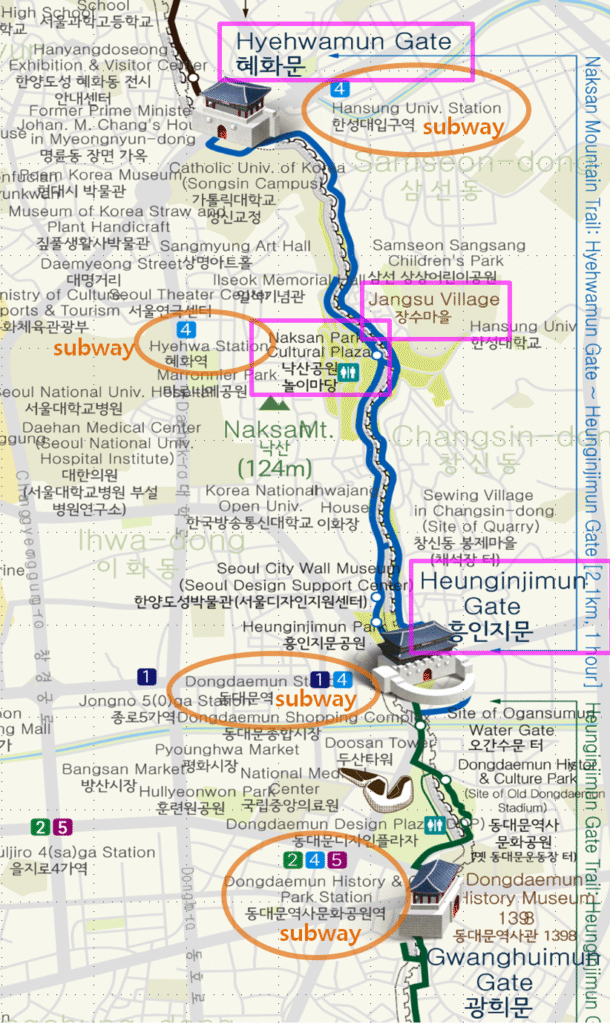

1. Beginner Route: Naksan Section (2km, 1-1.5 hours)

- Start: Hyehwa Station Exit 2 → Hyehwamun Gate

- End: Dongdaemun History & Culture Park

- You can also start from Dongdaemun History & Culture Park and walk the route in reverse.

- Highlights:

- K-Pop Demon Hunters filming location (hanok rooftop view)

- Dongdaemun night view (evening recommended)

- Section with most preserved inscribed stones

- Difficulty: Easy, mostly gentle slopes

2. Intermediate Route: Inwangsan Section (3.5km, 2-2.5 hours)

- Start: Dongnimmun Station → Donuimun Site

- End: Changuimun (Jahamun)

- Highlights:

- Harmony of natural rocks and fortress wall

- Seoul city view (especially sunset)

- Secret gate (ammun) discovery

- Difficulty: Moderate, some steep stairs

3. Advanced Route: Bugaksan Section (4km, 2.5-3 hours)

- Start: Changuimun (ID required)

- End: Sukjeongmun

- Highlights:

- Korean War bullet marks

- Barbed wire and CCTV (symbols of modern history)

- View of former Blue House (presidential office)

- Best-preserved original section

- Difficulty: Challenging, some steep sections

4. Complete Circuit: Full Loop (18.6km, 6-8 hours)

- Preparation: Plenty of water, snacks, stamina

- Recommendation: Complete in 2-3 days, dividing into sections

- Completion Certificate: Stamp tour program available at each section

Practical Information

- Operating Hours/Admission: 24-hour access, free admission

- Comfortable shoes essential (hiking boots or sneakers)

- Languages: English, Chinese, and Japanese information boards at major points

- Transportation: Most areas difficult to access by car; use subway

- Luggage Storage: Coin lockers available at most subway stations, costs ₩2,200-₩6,100 (4-hour basis) depending on size

- Restrooms: Public restrooms available along major sections

- Most accessible section: Naksan section (see Special Guide for K-Pop Demon Hunters Fans)

- Section characteristics: Bugaksan—best-preserved original wall; Inwangsan—exceptional city views; Naksan (see Special Guide for K-Pop Demon Hunters Fans)—gentle paths with great night views

- Caution on snowy/rainy days: Snow-covered fortress is beautiful but paths are slippery

Special Guide for K-Pop Demon Hunters Fans: Finding Those Scenes

Following Rumi’s Journey: K-Pop Demon Hunters Theme Circuit (2-3 hours estimated)

If you’re a K-Pop Demon Hunters fan, Naksan Park’s fortress trail is a must-visit. The scenes where Rumi and Jinu fight demons while discovering Seoul’s beauty and share deep conversations on hanok rooftops—they were born right here. Here’s a special route following the show’s major scenes:

1. Dongdaemun History & Culture Park (Start, Seoul Subway Lines 2 & 4)

- Early demon appearance scenes

- Space where modern and traditional collide

↓ (15-minute walk)

2. Heunginjimun (Dongdaemun)

- Major gateway of Joseon Dynasty

- Symbol of city defense in the show

↓ (20-minute walk)

3. Naksan Park Fortress Trail ⭐ Main Spot

- Rumi-Jinu conversation scene

- “Free” song backdrop

- Recommend staying 30+ minutes for photos

↓ (20-minute walk)

4. Hyehwamun Gate

- Observe inscribed stones

- Traces of 600 years of history

↓ (15-minute walk)

5. Daehangno Cafe Street

Below is a guide map centered on the Naksan route. For the complete Seoul City Wall map and guidebook, refer to this link: https://seoulcitywall.seoul.go.kr/index.do

Map source: Seoul Metropolitan Government Seoul City Wall website