Jeongdong-gil: The Center of the Daehan Empire’s Political and Diplomatic Struggles

In the heart of Seoul, a 2.6km path called Jeongdong-gil runs alongside the stone walls of Deoksugung Palace. Despite being surrounded by high-rise buildings, this small street has long been cherished by Koreans. Walking along this path, visitors find the palace walls, century-old Western-style buildings, and ginkgo trees harmoniously blended together, offering a beautiful sense of the changing seasons even in the heart of the city.

This area is home to red brick churches, Western-style stone buildings, and hilltop towers built over a century ago—structures that appear distinctly foreign to most Koreans. In the late 19th century, this was the epicenter where the Daehan Empire and Western powers engaged in intense diplomatic competition. Behind its beautiful scenery lies the deep struggles of Korea’s modern history.

Daehan Empire: Korea’s last absolute monarchy that existed from 1897 to 1910. Emperor Gojong ascended to the throne and declared the nation’s sovereign independence, attempting modernization reforms in domestic politics, military, commerce, industry, and education. However, following the Sino-Japanese War and Russo-Japanese War, Japan’s growing influence led to the empire’s downfall.

1882: The Door to Modernization Opens

In the late 19th century, Western powers strengthened by the Industrial Revolution pursued imperialism, colonizing Africa and Asia. The 1890s particularly saw Russia’s eastward expansion, America’s westward movement, and Japan’s territorial ambitions all converging on East Asia. The Korean Peninsula stood at a crucial geopolitical crossroads where these competing powers clashed.

Beginning with the Treaty of Peace, Amity, Commerce, and Navigation with the United States in 1882, Korea established official diplomatic relations with Western nations. The United States, Great Britain, Russia, France—each country rushed to establish legations in Seoul. Jeongdong became the center of this diplomatic activity because of its proximity to Deoksugung Palace, where the royal family resided.

In 1885, American missionaries arrived, bringing churches and schools to the area. Jeongdong transformed into a “miniature international city” where diplomacy, religion, and education converged. Even today, embassies from many of these nations that first established ties with Korea still maintain their presence here.

Deoksugung Palace and Seokjojeon Hall:

A Palace Built on Imperial Dreams

A walk along Jeongdong-gil begins at Deoksugung Palace. Upon entering through the main gate, one building immediately captures attention: Seokjojeon Hall. Standing majestically among traditional Korean pavilions, this Western-style palace creates the illusion of being in a European city.

Seokjojeon, meaning “Stone Palace,” was constructed over a decade from 1900 to 1910. Designed by British architect J.R. Harding in neoclassical style, this three-story stone building features granite walls and Ionic columns.

Emperor Gojong—the 26th king of Joseon and the first emperor of the Daehan Empire, who reigned from 1863 to 1907 through turbulent times and attempted various modernization reforms but ultimately lost national sovereignty to Japanese imperialism, leaving him remembered as a tragic monarch—decided to build a Western-style palace rather than a traditional Korean one. His purpose was to proclaim the Daehan Empire as a sovereign modern nation and symbolically demonstrate the dignity and authority of an imperial state. By adopting Western architectural styles using stone rather than traditional wooden construction, he sought to showcase the nation’s acceptance of Western civilization and its determination to build autonomous strength through modernization.

Seokjojeon housed reception rooms, a grand dining hall, living quarters, bedrooms, and even Western-style bathrooms. Emperor Gojong used this space to receive foreign envoys and hold imperial ceremonies in his efforts to elevate the Daehan Empire’s international standing. It also served as his office and residence.

Jeongdong First Methodist Church: A Space of Faith and Resistance

Leaving Deoksugung and entering Jeongdong-gil, visitors encounter an elegant church built with red brick. Completed in 1897, Jeongdong First Methodist Church represents Korea’s first Protestant chapel in Victorian Gothic style and was the first to install a pipe organ in Korea.

After American missionary Henry Appenzeller held the first service here in 1885, Jeongdong First Methodist Church became more than just a religious space—it emerged as an important stage in Korea’s modern history.

When Empress Myeongseong was assassinated by Japanese forces in the 1895 Eulmisabyeon (Eulmi Incident)—Empress Myeongseong was both Emperor Gojong’s wife and political partner, standing in political opposition to Gojong’s father, the Heungseon Daewongun. As Japan prepared for war with Russia, Japanese soldiers and hired thugs brutally murdered the empress, who had been strengthening ties with Russia—a memorial service was held at this church. During the March 1st Independence Movement of 1919, Pastor Lee Pil-ju and Evangelist Park Dong-wan participated as part of the 33 National Representatives. Yu Gwan-soon, a student at Ewha Haktang who attended this church, joined fellow church members in the independence demonstrations.

The church courtyard features a tile map of old Jeongdong. This map reveals how many foreign legations, schools, and hospitals were concentrated in the area. Jeongdong served as Korea’s gateway to the world, and this church stood at its center, sharing in the nation’s suffering.

Yu Gwan-soon (유관순, 柳寬順) was a prominent Korean independence activist and a symbol of the March 1st Movement (삼일운동, or Samil Undong) against Japanese colonial rule in 1919

Former Russian Legation Site: The Hill Where an Emperor Sought Refuge

Following Jeongdong-gil up a hill leads to a small park. There stands a lonely white stone tower—the only remaining trace of the old Russian Legation.

In the early morning of February 11, 1896, Emperor Gojong secretly escaped the Palace in a palanquin disguised as court ladies’ transport and took refuge at the Russian Legation. History calls this event Agwan Pacheon (The Emperor’s Refuge at the Russian Legation).

Why did the emperor flee his own palace for a foreign legation? At that time, Korea stood caught in the middle of a power struggle among Japan, Russia, and other great powers. After Empress Myeongseong was assassinated by Japanese forces in 1895, the emperor feared for his own safety. To counterbalance Japanese influence, he sought Russia’s protection and escaped his palace to take shelter at the Russian Legation.

Gojong remained at the hilltop legation for nearly a year. The fact that an emperor conducted state affairs from foreign soil rather than his palace demonstrates how precarious the Daehan Empire’s situation had become. What thoughts occupied the emperor’s mind as he gazed down at Deoksugung from this hill?

Nearby stood the Sontag Hotel, operated by Antoinette Sontag, wife of the Russian diplomat. Emperor Gojong is said to have tasted coffee for the first time here, marking the beginning of Korean coffee culture.

Ewha Haktang and Paejae Haktang: Sparks of Modern Education

In 1885, two revolutionary schools opened in Jeongdong: Ewha Haktang(Hakdang refers to a school or academy in the late Joseon Dynasty.) founded by American missionary Mary Scranton, and Paejae Haktang, established by Henry Appenzeller.

Ewha Haktang was Korea’s first women’s educational institution. In an era when female education was taboo, this school taught Korean, English, mathematics, and science. Though it began with just one student, growing numbers of women eventually received modern education here and experienced a new world. Many independence activists, including Yu Gwan-soon, were Ewha Haktang graduates.

Paejae Haktang also pioneered modern education. Rather than traditional Confucian learning, it taught Western science and democratic ideals, with students learning debate and public speaking. The East Hall of Paejae Haktang (a 1916 building) remains today as precious evidence of that era’s educational fervor.

These two schools were more than just places of learning. They planted the seeds of egalitarian ideals—that anyone could receive education regardless of class or gender—and nurtured young people’s hopes for building a sovereign modern nation.

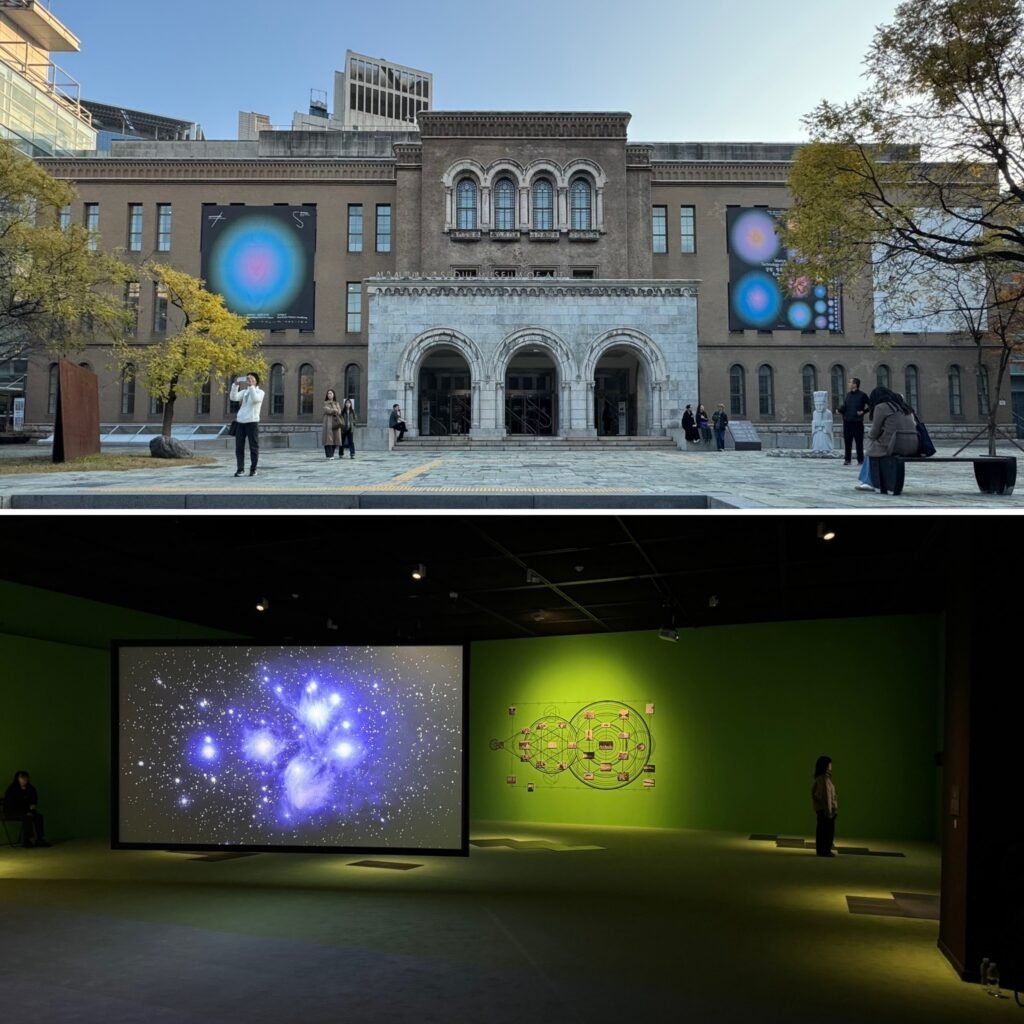

Seoul Museum of Art: The Former Supreme Court of the Daehan Empire

Originally the Daehan Empire’s Supreme Court, this Renaissance-style building was constructed in 1928 using the architectural styles of that period. It served as the supreme court during Japanese colonial rule, then as the Supreme Court of the Republic of Korea after 1948. During the early Korean War, when North Korea briefly occupied Seoul, it was temporarily used as the Seoul branch of the Korean Workers’ Party.

Today, the museum hosts various exhibitions and educational programs related to contemporary art, with many free exhibitions available. The museum’s entrance path extending from Jeongdong-gil and the peaceful atmosphere of the courtyard are particularly appealing.

Epilogue: History Compressed into 2.6km

Jeongdong-gil may be just a 2.6km walking path, but it compresses the turbulent modern history spanning from Joseon to Korea. It is a road that penetrates through the 1880s diplomatic quarter, the 1890s great power competition, the 1900s Daehan Empire’s modernization efforts, and the tragedy of losing national sovereignty in 1910.

Walking slowly along the palace stone walls beside Jeongdong-gil, where time seems to have stopped, one can travel back 150 years in imagination: seeing the emperor’s dreams of Korean modernization at Seokjojeon Hall; feeling citizens’ determination to reclaim stolen national sovereignty at Jeongdong First Methodist Church; recalling the Daehan Empire caught in the whirlpool of cold international politics at the former Russian Legation site; and sensing the passion of young people striving to become global citizens at the sites of the schools. These are the special emotions that Jeongdong-gil evokes.

Visitor’s Guide

- Location: Jeongdong-gil, Jung-gu, Seoul (Exit City Hall Station, Subway Lines 1 & 2)

- Recommended hours: 10:00 AM – 4:00 PM

- Duration: 2–3 hours

- Advance reservation required for Seokjojeon Hall at Deoksugung Palace

- Best seasons: Fall (October–November) and Spring (April–May)

- Walking Jeongdong-gil alongside the fallen leaves on Deoksugung’s stone wall path offers one of Seoul’s most romantic strolls