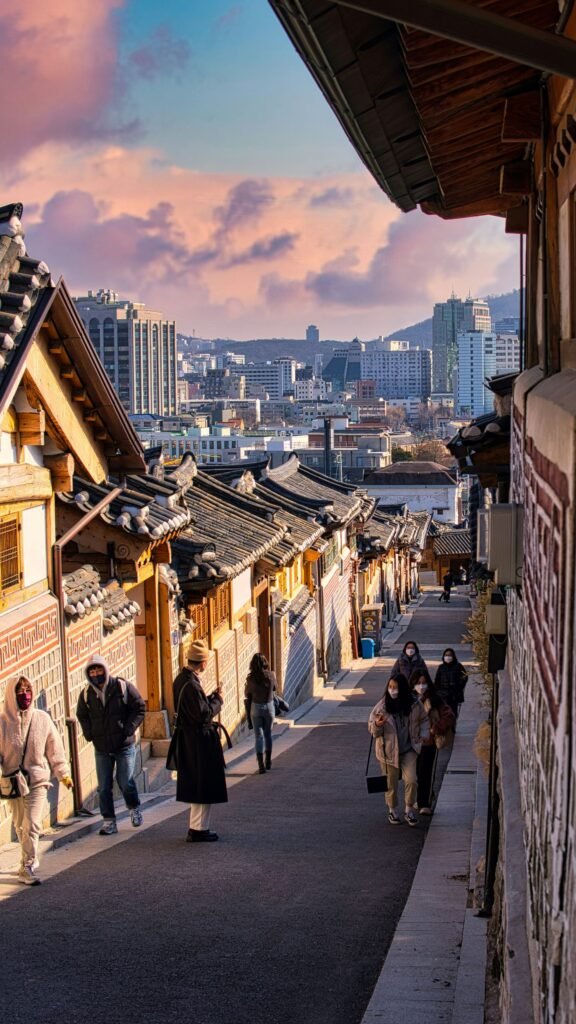

Step out of Exit 4 at Jongno 3-ga subway station, and you’ll encounter a landscape where time seems to blend together. Between towering office buildings, narrow alleyways appear, lined on both sides with tile-roofed houses packed tightly against one another.

This hanok residential area, established a century ago, now bustles with twenty-somethings queuing for salt bread, couples taking selfies over flat whites in hanok cafe courtyards, and groups gathered around grills or street-side tables downing draft beer.

Developed as Working-Class Housing 100 Years Ago

Ikseon-dong’s history began alongside Korea’s modern era. In the 1920s, a company called Geonyang-sa developed this area into Korea’s first “improved hanok residential complex.”

The project was led by Jung Se-kwon, a real estate developer who was also an independence activist. Based on traditional Joseon hanok architecture, he created a new residential form called “urban hanok”—structures designed to efficiently utilize limited urban land.

Designed to house families of six, these homes featured a maru¹—similar to today’s living room—as the central space, with rooms arranged compactly yet efficiently around it. They included running water and electricity, and relocated the traditional outdoor toilet inside the house—all remarkably modern features for the time.

Jung Se-kwon responded to the residential expansion of Japanese colonizers by enabling ordinary Koreans to establish themselves in the city. Rather than requiring large upfront payments, he introduced “monthly installment sales”—essentially implementing the concept of modern mortgage financing in the 1930s. This made homeownership accessible to working-class families, and people from the middle class and below moved in en masse.

¹ Maru: A traditional Korean wooden-floored space that serves as a transitional area between rooms, functioning similarly to a modern living room.

Subsequently, Ikseon-dong established itself as a typical working-class Seoul neighborhood. After independence from Japan in the 1940s, it filled with refugees and migrants from rural areas. During the industrialization period of the 1960s-70s, countless Seoul residents built their lives here.

Becoming an Island in the City

The old Ikseon-dong, true to its working-class roots, had tailor shops, watch repair shops, and tobacco stores in every alley. The area housed many upscale restaurants called yojeong²—one of which hosted discussions leading to the July 4th South-North Joint Statement³ in 1972.

² Yojeong: Traditional high-end Korean restaurants that combined dining with entertainment, often featuring traditional music and dance performances.

³ July 4th South-North Joint Statement: A historic 1972 agreement between North and South Korea outlining principles for peaceful reunification.

However, from the 1980s onward, with Gangnam’s development and the apartment boom, Ikseon-dong gradually faded from memory. Life in aging hanoks became inconvenient, and residents began leaving one by one. In 2004, Ikseon-dong was designated for redevelopment—the hanoks were to be demolished and replaced with apartments.

But the redevelopment collapsed amid residents’ conflicting interests, leaving only empty hanoks in the alleys—a space where time truly stood still.

The Appeal Created by Young Artists and Small Business Owners

In 2014, fashion photographer Lewis Park converted three empty hanoks into Cafe Singmul (meaning “Plant”). Unable to afford high rents elsewhere, Ikseon-dong’s affordable hanoks offered him an opportunity. But rather than simply opening a business, he created an atmospheric space that preserved the hanok’s character. Green plants flourished beneath tile roofs, and coffee aromas wafted through the courtyard. He also used the space for exhibitions.

Singmul’s success triggered a chain reaction. Young entrepreneurs successively renovated hanoks into cafes and shops. Coinciding with Instagram’s rise in popularity, Ikseon-dong’s distinctive landscape spread rapidly through social media.

After 2015, cafes, bakeries, bars, and restaurants filled the narrow alleys, dramatically transforming Ikseon-dong. Combined with the newtro⁴ (new-retro) trend, millennials and Gen Z—who hadn’t experienced this past—flocked to the area.

⁴ Newtro: A Korean portmanteau of “new” and “retro,” describing the trend of reinterpreting and consuming past aesthetics through a contemporary lens.

Spaces preserved hanok structures while modernizing interiors, craft beer enjoyed under tile roofs, neon signs visible through traditional paper doors—all these contrasts became Ikseon-dong’s unique charm.

Comparing Hanok Villages: Bukchon vs. Ikseon-dong

Though both are hanok villages, experiences in Bukchon and Ikseon-dong differ markedly. Bukchon is a refined hanok village preserved under government leadership—with wide alleys, large hanoks, and protected status as a tourist destination. Since actual residents still live there, signs request visitors keep noise levels down.

In contrast, Ikseon-dong’s hanoks line alleys so narrow two people can barely pass. These spaces emerged when young entrepreneurs accidentally discovered the area’s potential after redevelopment failed and injected their creative ideas. This “unplanned coincidence” created today’s vibrant Ikseon-dong.

If Bukchon is a hanok village for “viewing,” Ikseon-dong invites you inside to enjoy many urban pleasures—cafes and bakeries, bars, modern crafts, even barbecue.

Time Out, a global online media outlet specializing in culture and entertainment, ranked Jongno 3-ga—which encompasses Ikseon-dong—third in its “29 Coolest Neighborhoods in the World” for 2021.

Shadows Cast Over Ikseon-dong’s Alleys

As everywhere, Ikseon-dong’s success created new problems. While alleys bustle with weekend tourists, soaring rents forced out the creative small business owners who revitalized the area. Well-capitalized franchises and corporations have moved in instead.

There are local residents whose daily lives suffer from crowding tourists, and shopkeepers sighing over burdensome rent increases.

While hanok exteriors remain, shops with interiors excessively renovated or haphazardly remodeled for business convenience—disregarding traditional architectural principles—draw criticism from those who respect hanok identity.

Nevertheless

Ikseon-dong’s dilemma mirrors those of Hongdae, Gyeongridan-gil, and Yeonnam-dong: balancing cultural value with commercial success, enabling coexistence between original residents and visitors, questioning boundaries between preservation and utilization—problems without easy answers.

Nevertheless, Ikseon-dong remains a meaningful space. Despite commercialization’s shadow, it demonstrates that traditional hanok architecture can be both attractive and functional through contemporary use.

What matters is that these changes emerged from pure, organic motivations—not government planning or corporate capital, but individual entrepreneurs’ creativity and young consumers’ sensibility—ultimately creating a space worth visiting and experiencing.

If people from a century ago—when these hanoks were completed through a businessman’s commercial needs mixed with patriotic motivation—could see today’s Ikseon-dong, what would they think?

Would they wonder: “Why are so many people crowding into these cramped alleys? What are all these shops, and why are people queuing like that?”